教室計畫 (2009-2015)

創作自述

教室是微觀下的權力場域。

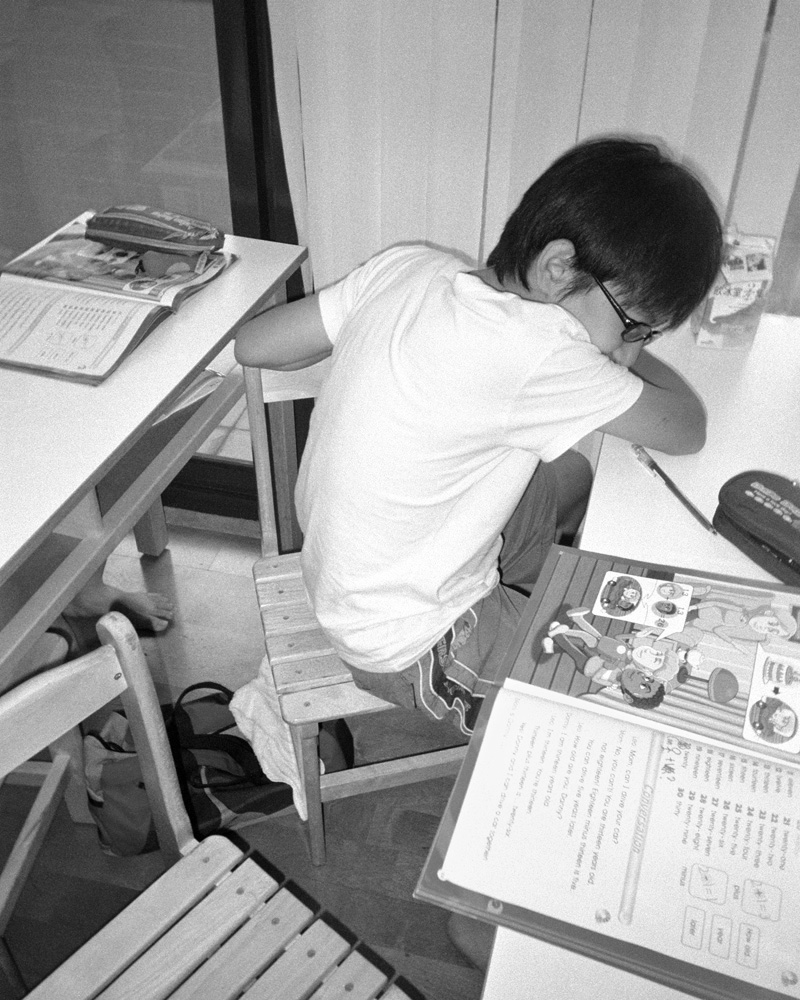

我,一個兼職英語老師、一個攝影者、一個大人,站在權力傾斜的這一端;另一端,是我的學生、我的被攝者、一群兒童。

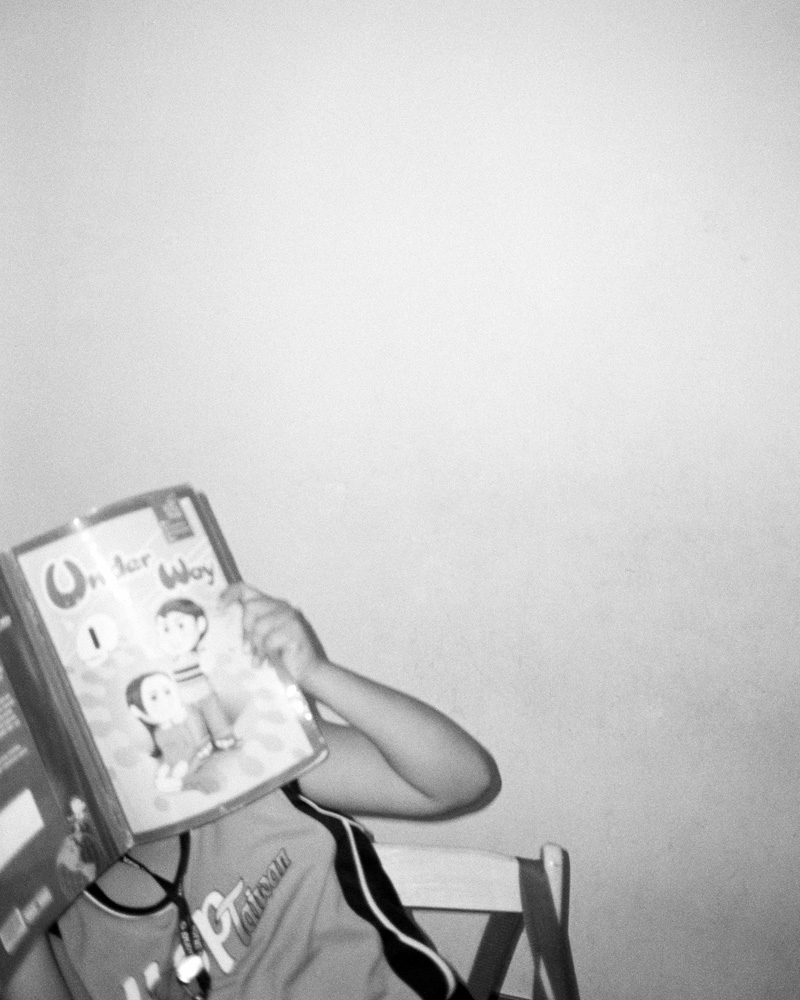

某個近乎遊戲的機緣下,我開始試著以相機「記錄」學生不守規矩、脫序的偶發表現,打算以如此真實直接的「呈堂證供」,向家長們好好告上一狀。當我舉起相機、將鏡頭對著調皮搗蛋的學生時,我赫然意識到這項行動的多重侵略性。轉瞬間,教室從學習輔導的場所變成權力交錯的熱區,一個我和學生親身參與、演練的田野。

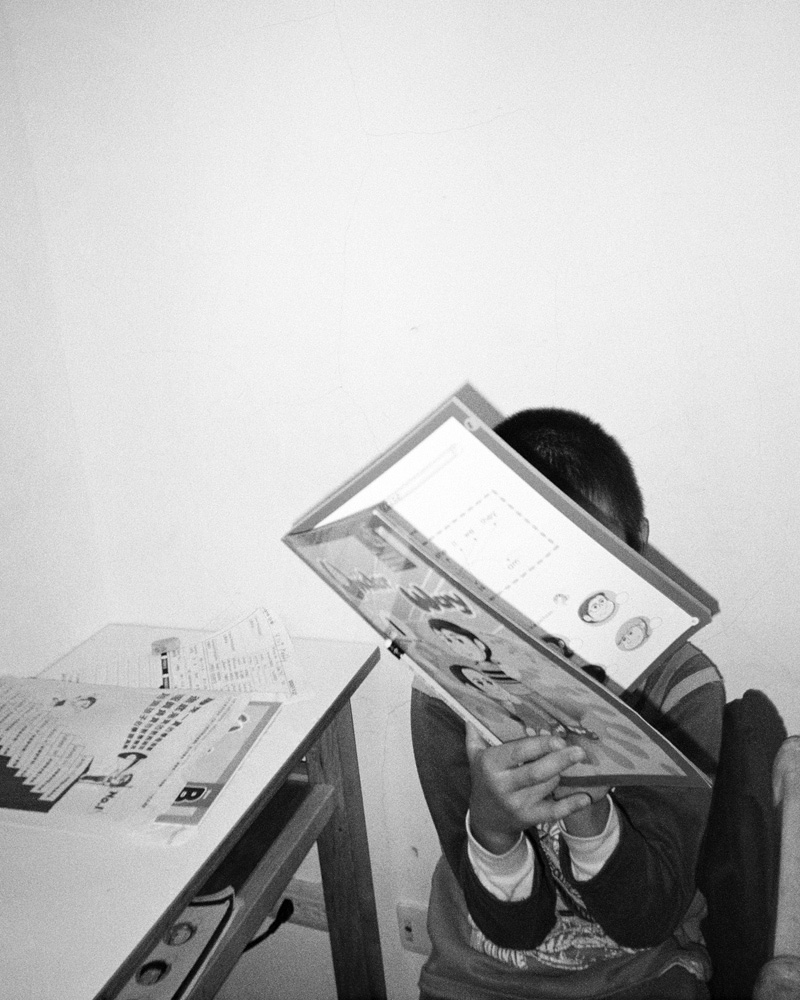

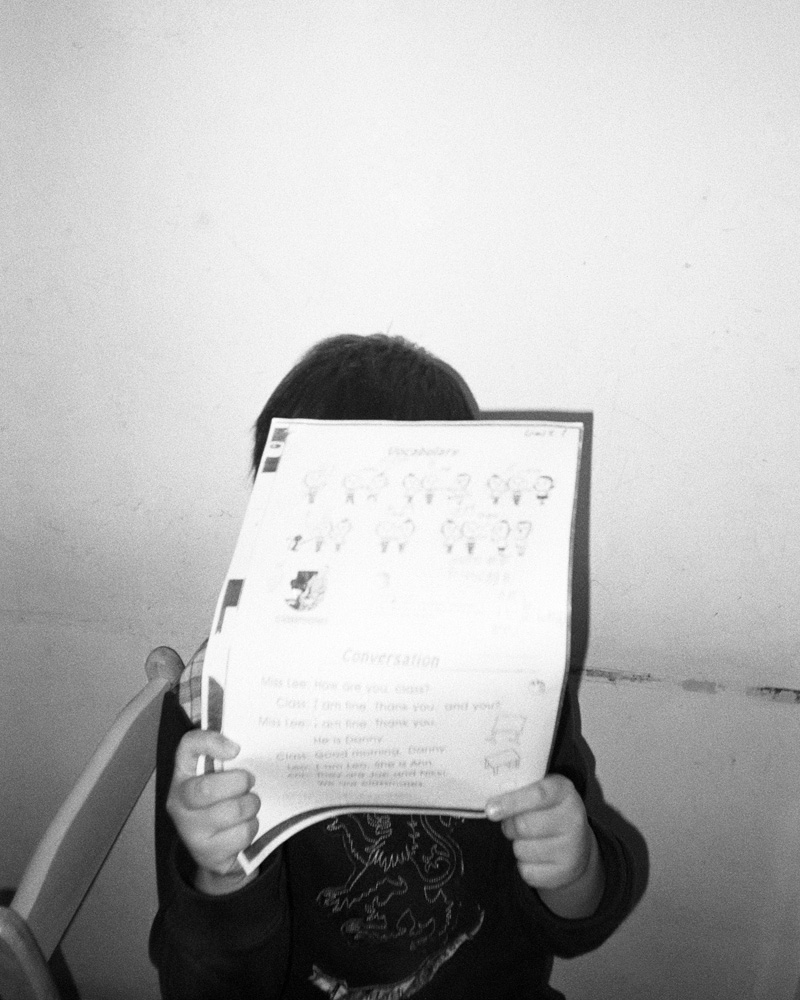

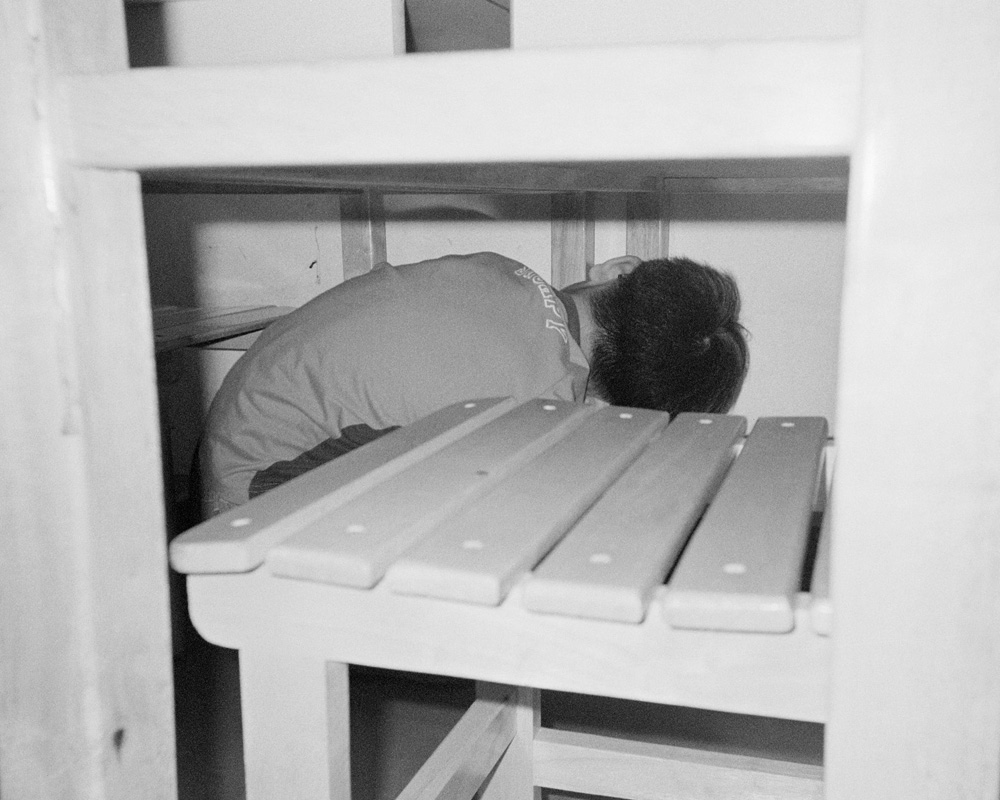

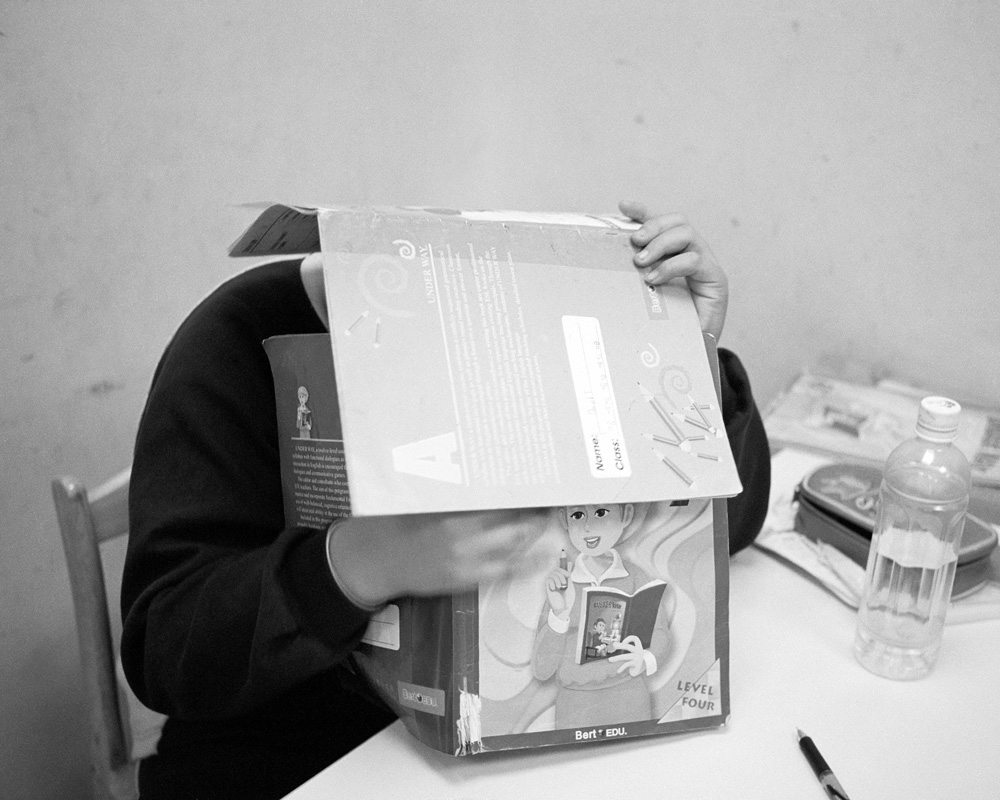

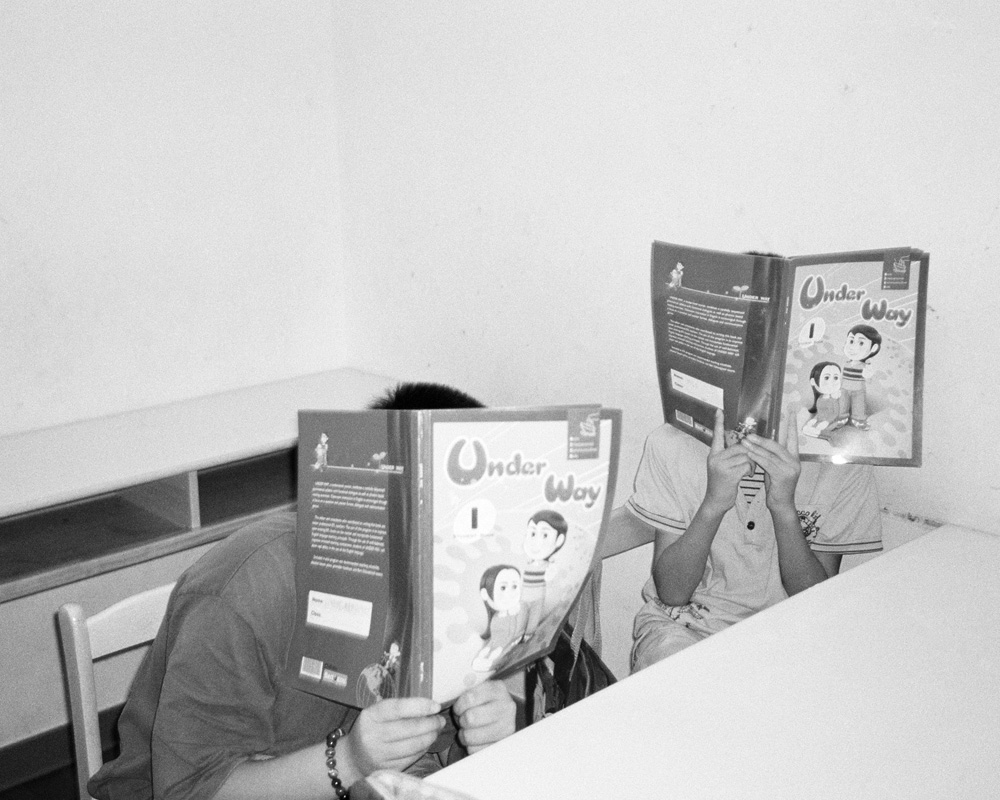

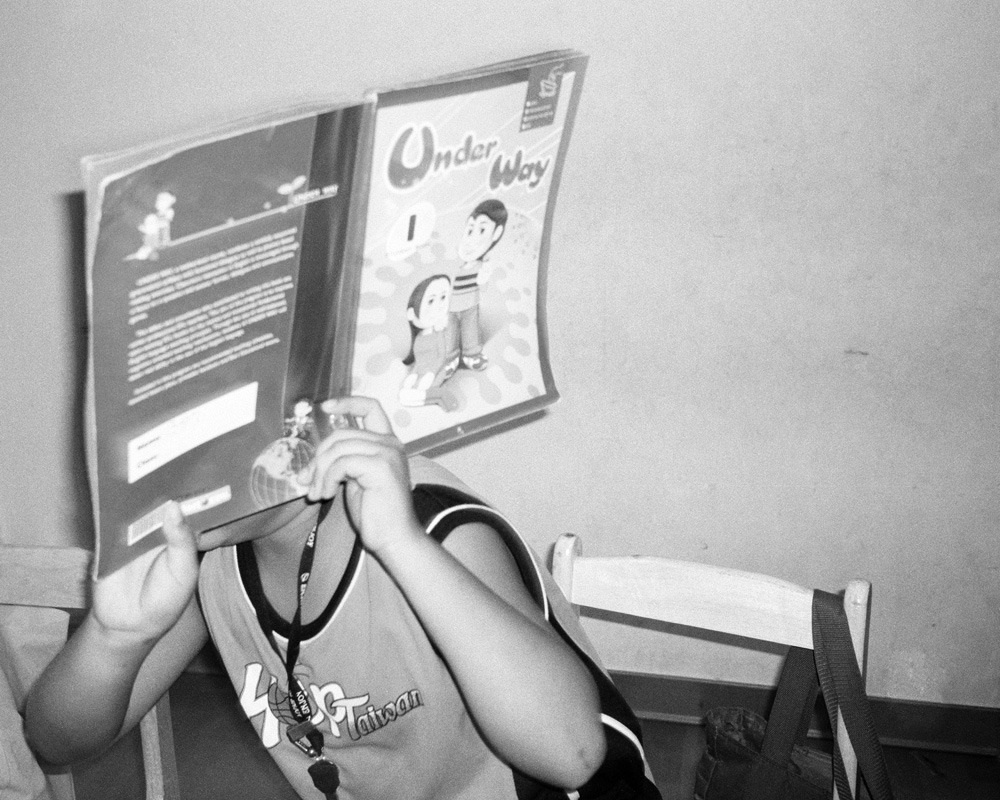

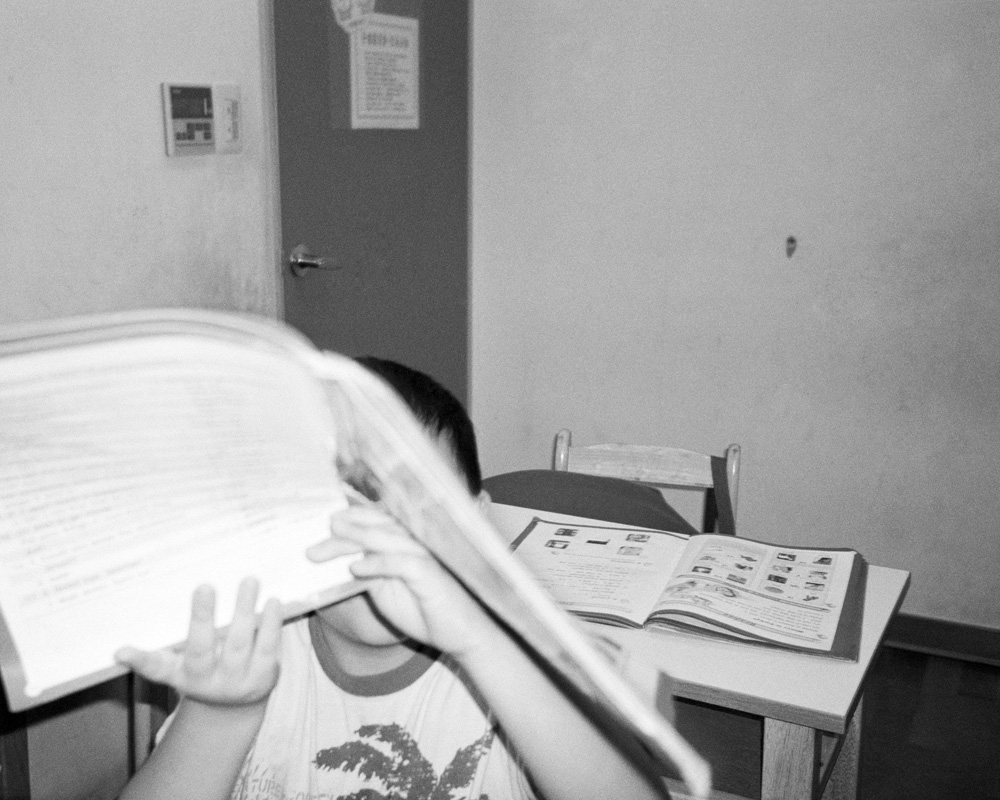

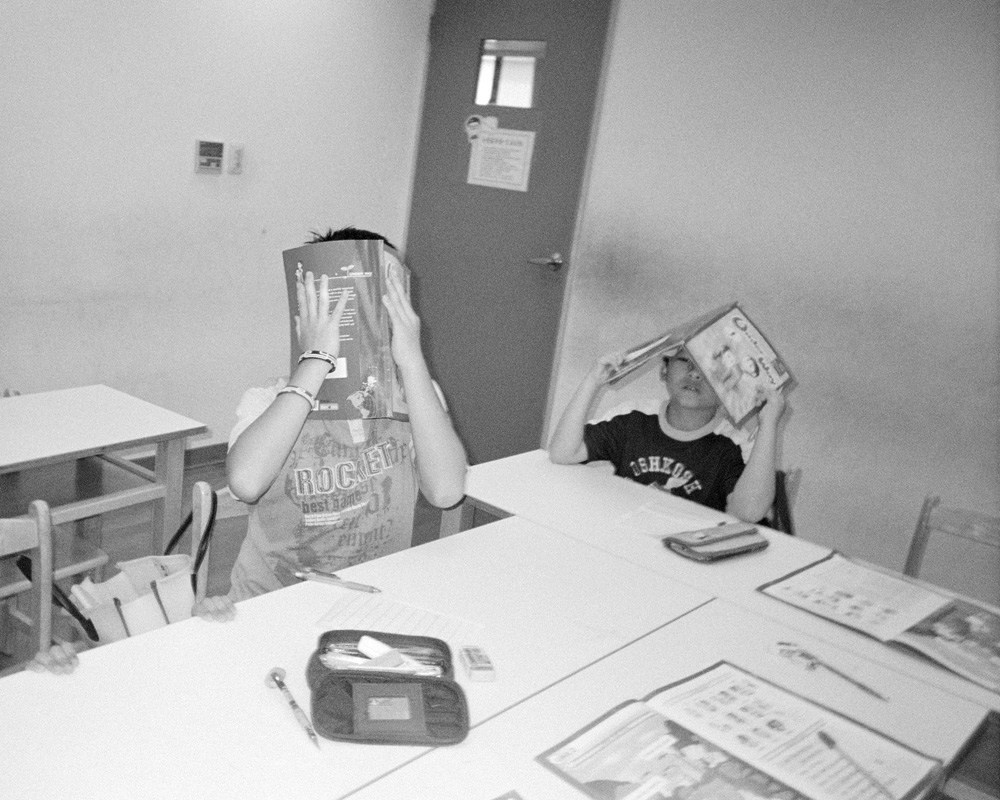

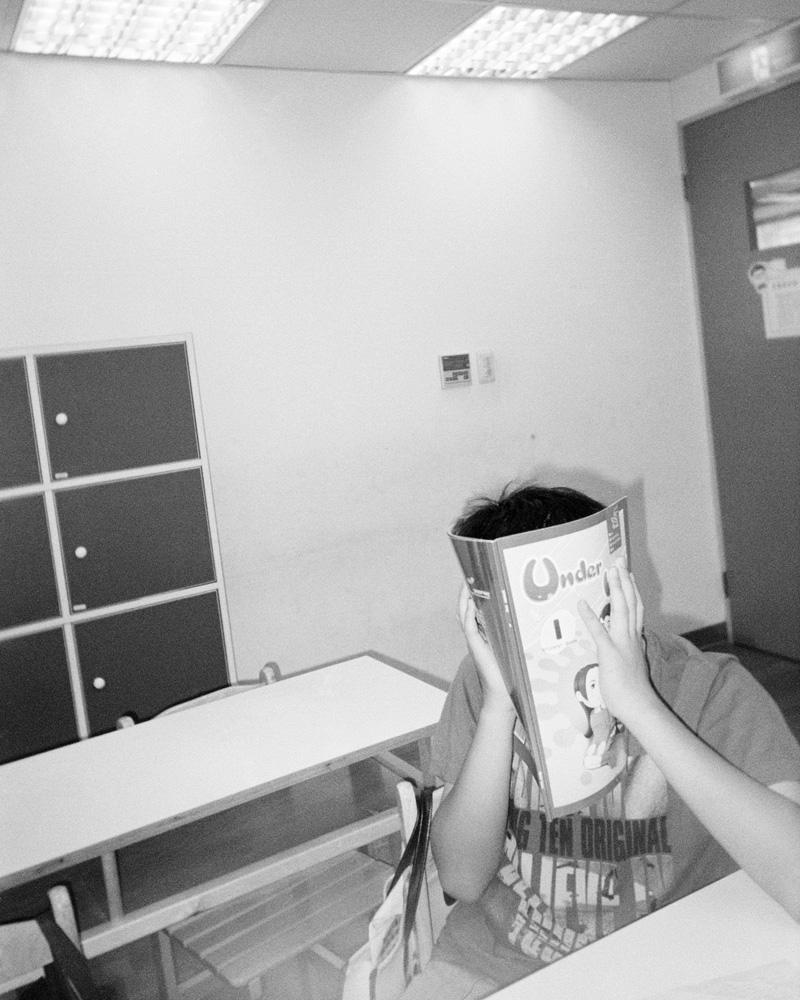

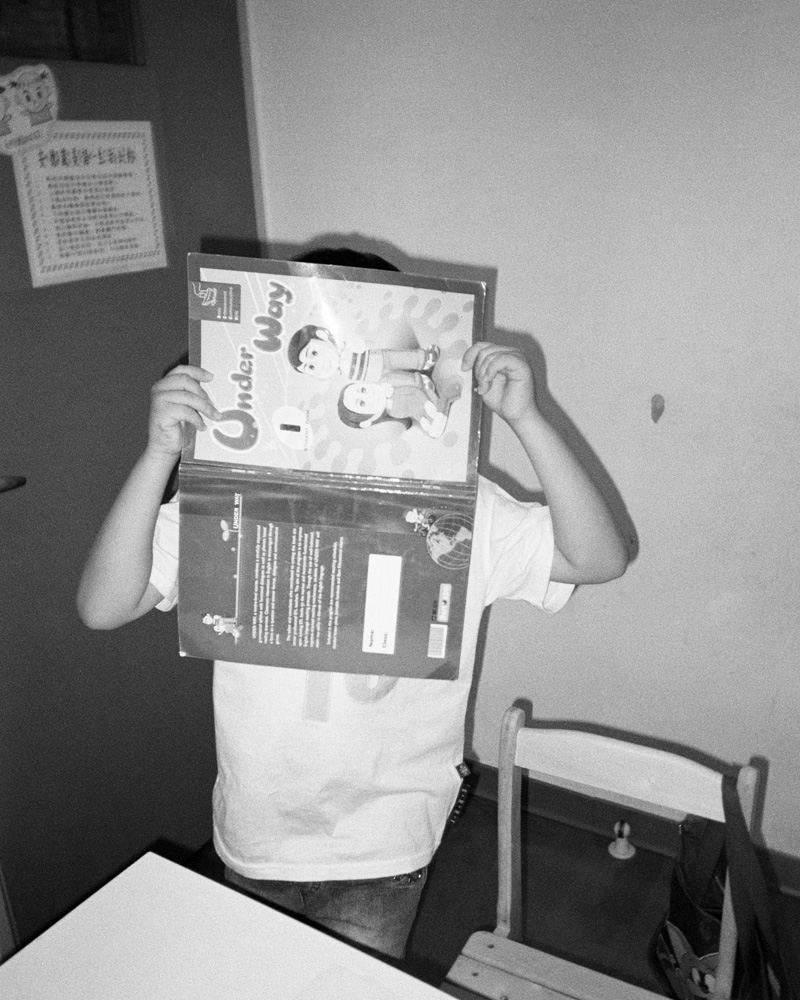

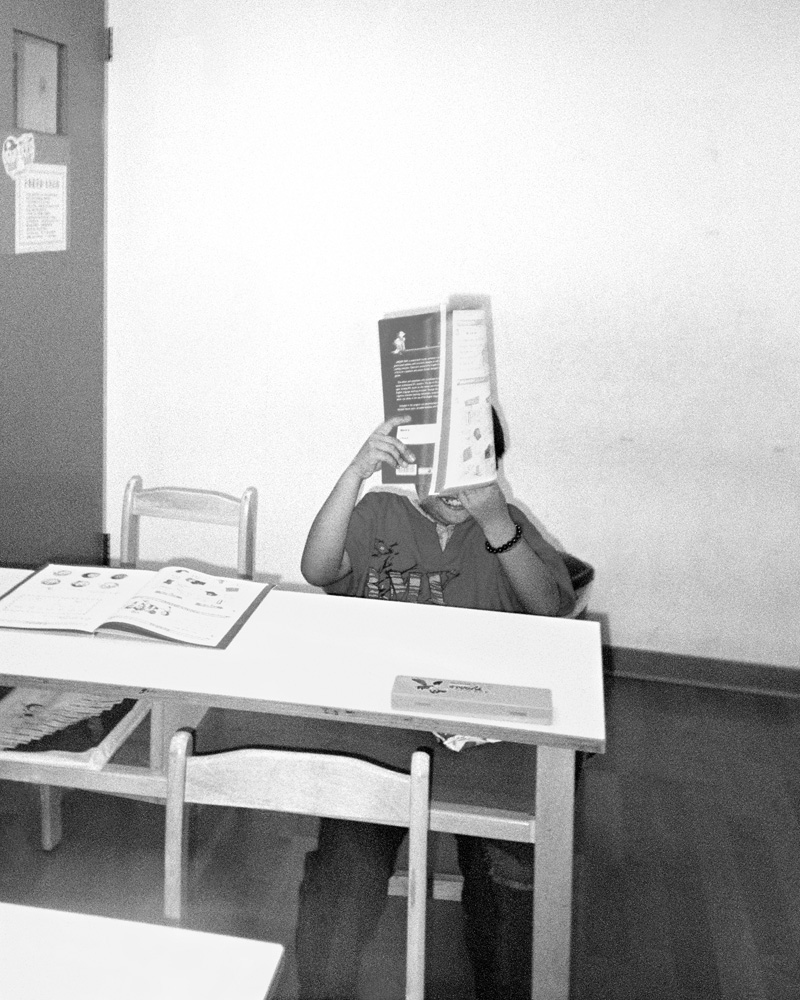

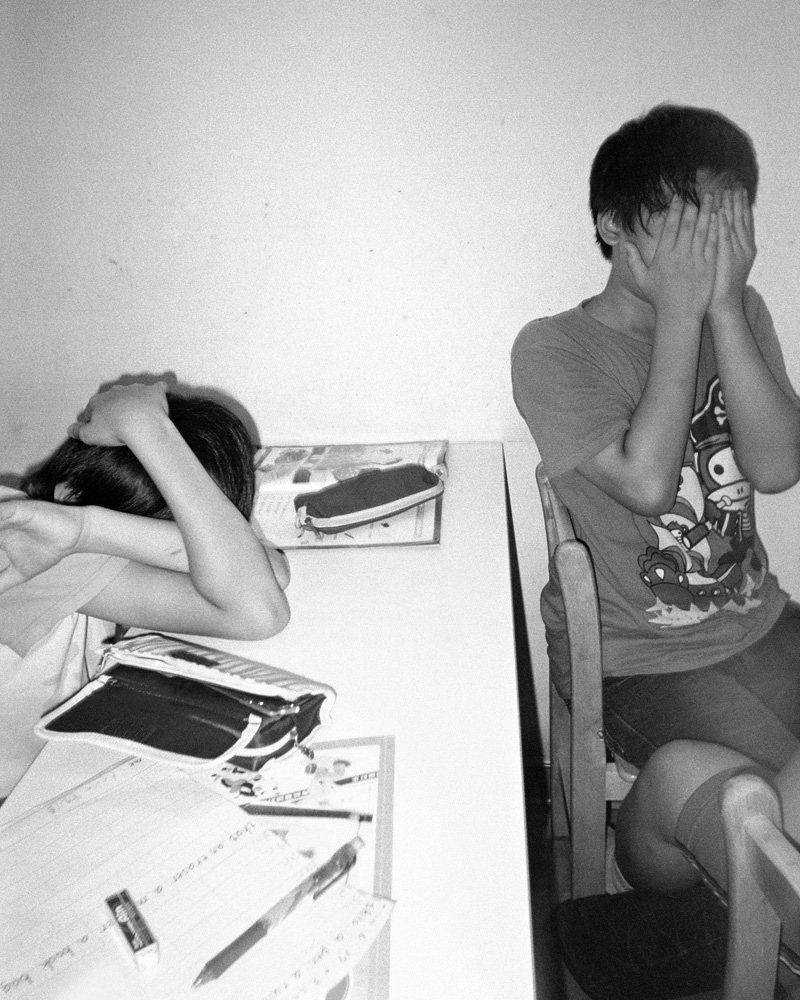

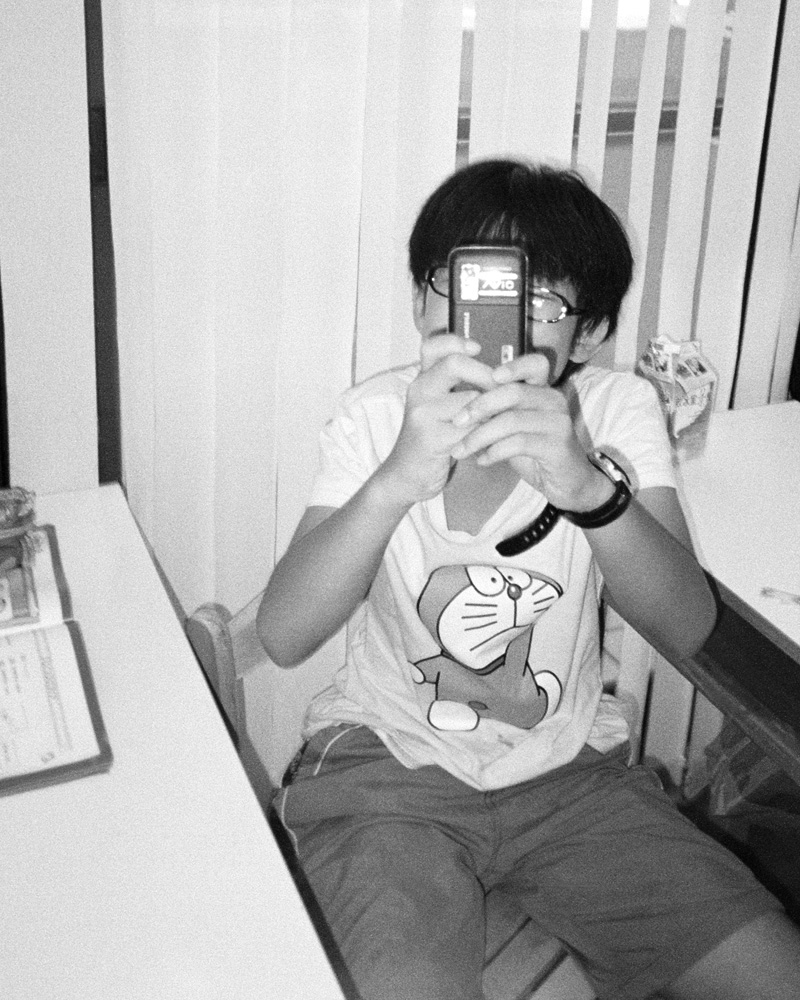

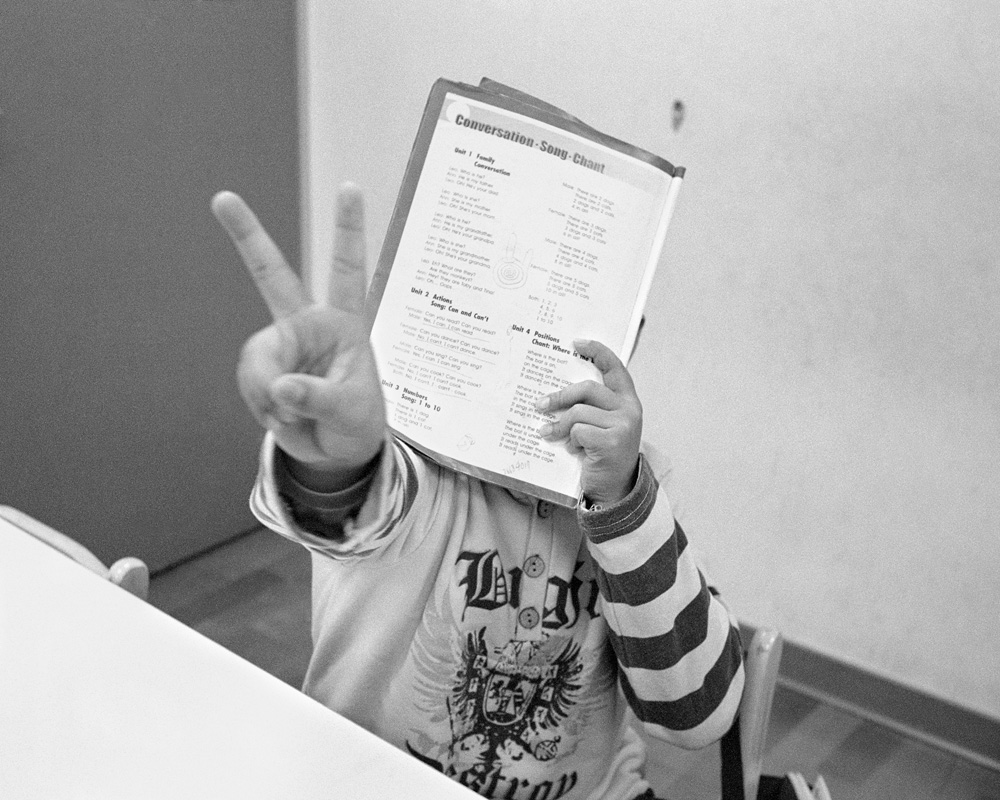

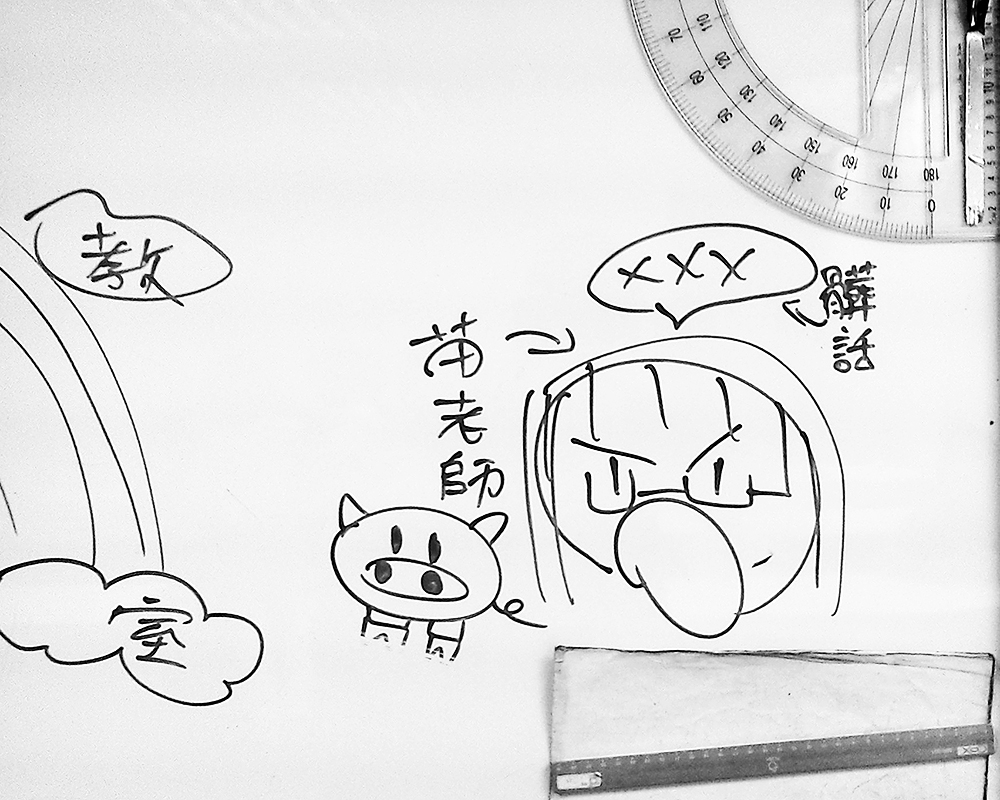

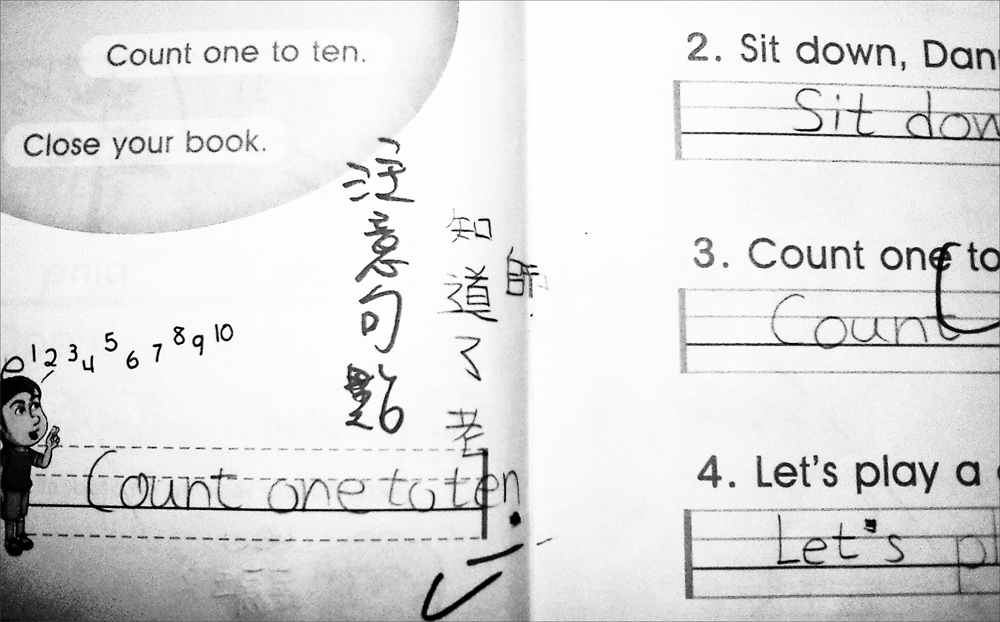

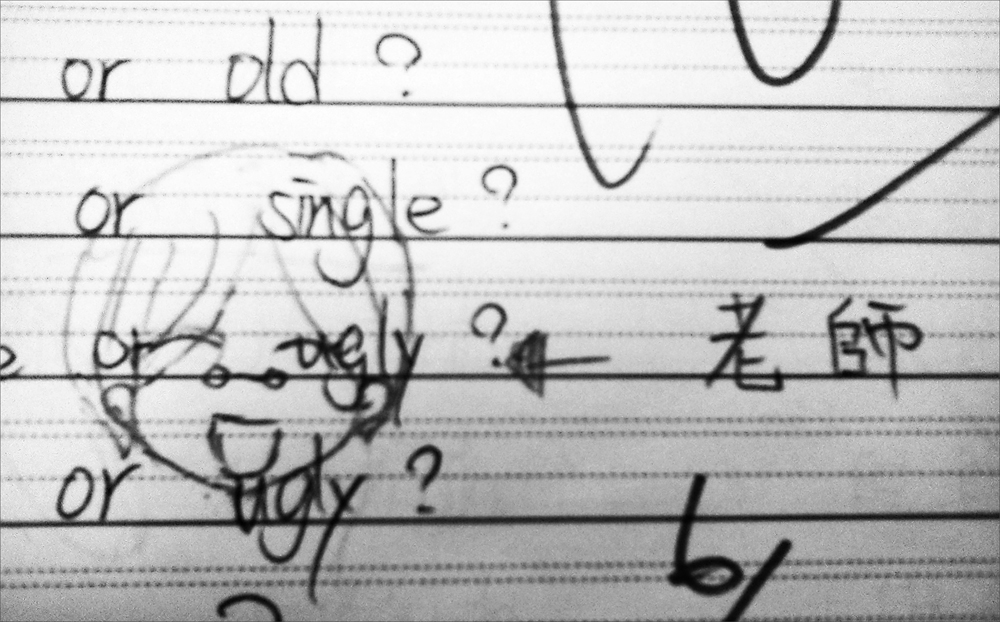

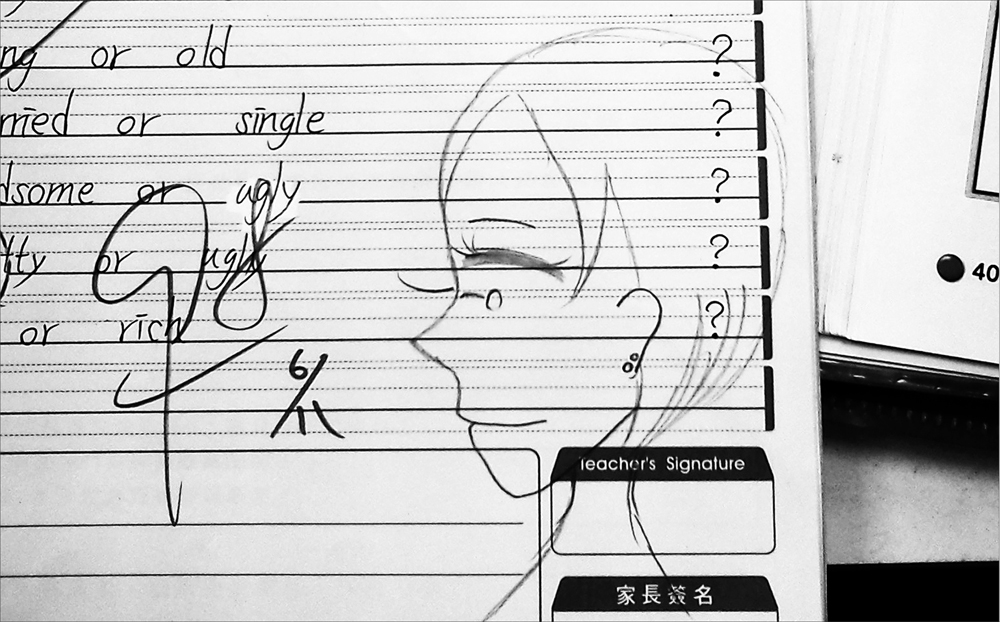

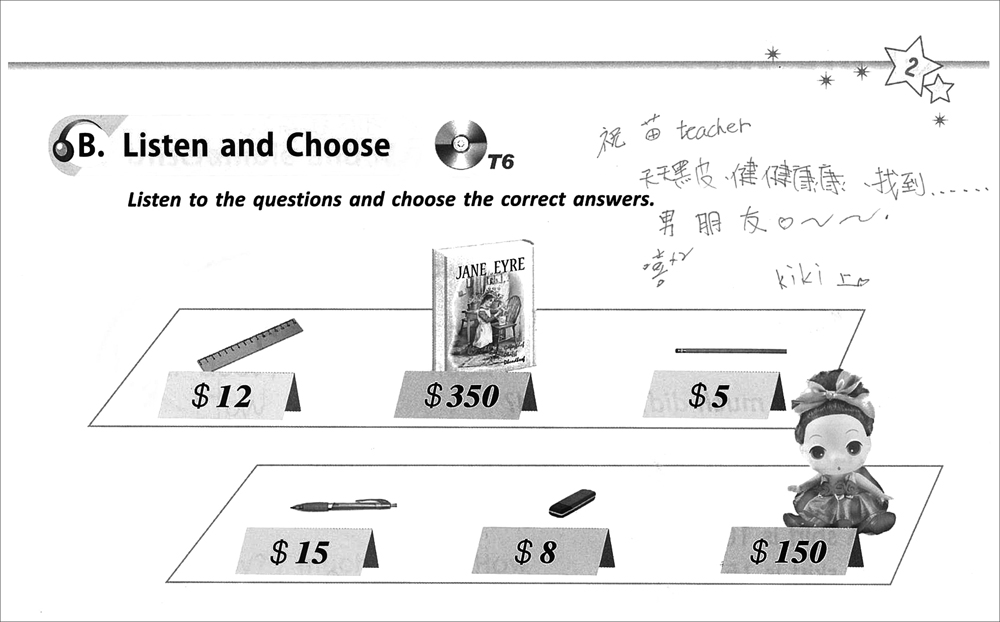

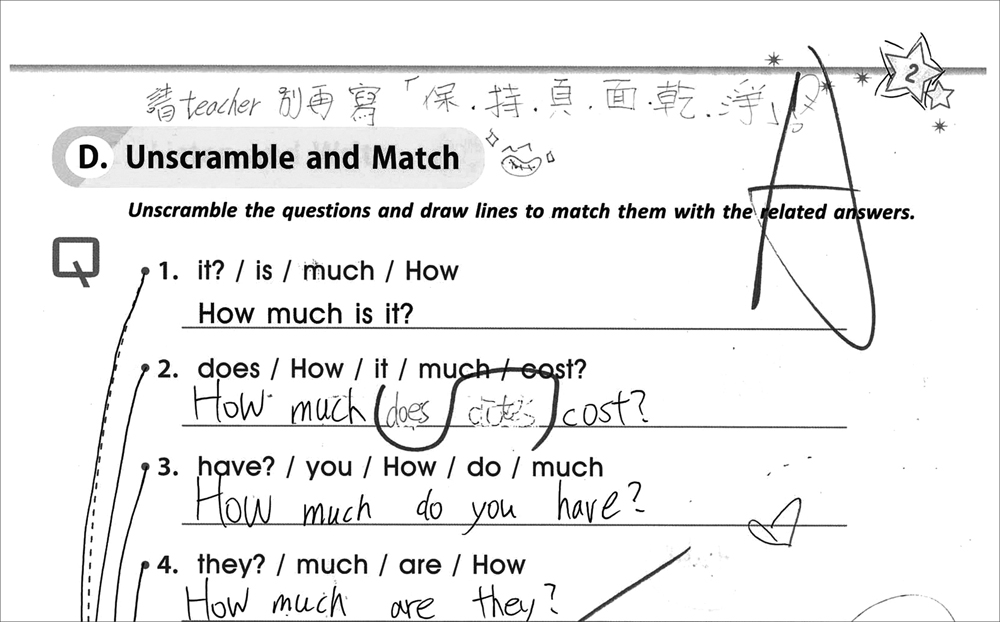

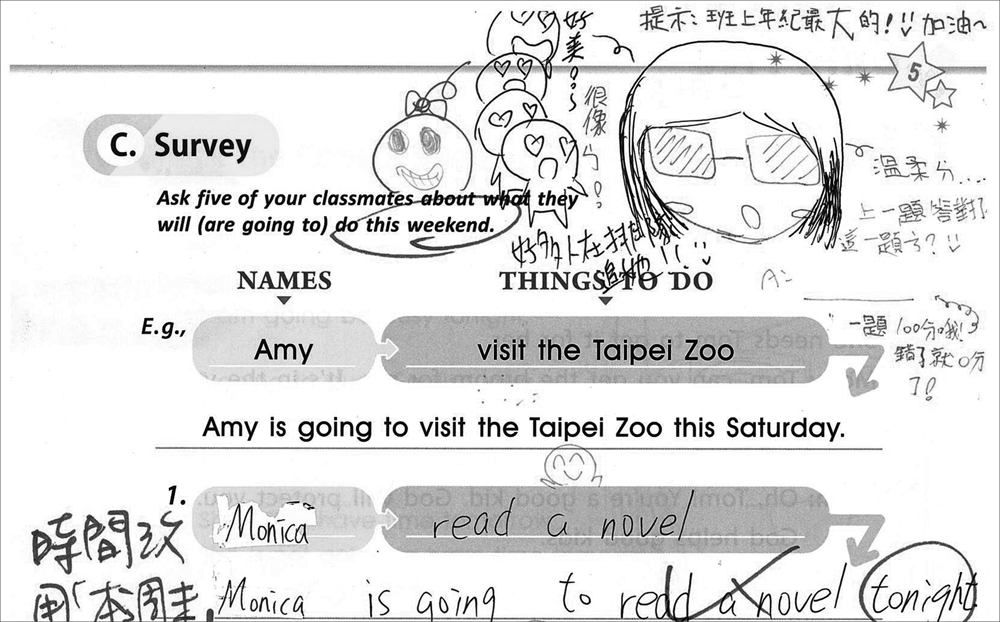

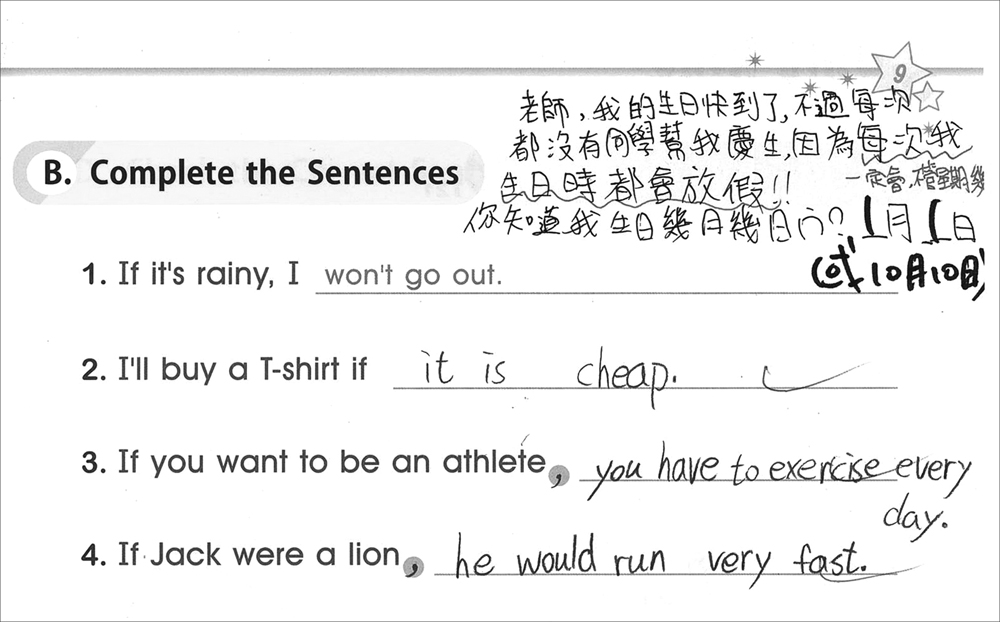

然而,這樣以相機捕捉失序行為的企圖,只顯示了失敗;以為可藉此留下真實影像證據的攝影者,留下的是讓自己尷尬的天真與啞然失笑。沒有決定性的瞬間。什麼都沒記錄到。照片裡看不到脫軌的行徑,只有難以辨識、面目模糊的嫌疑人,以及一次又一次的脫逃或抵抗。孩子們以猶如游擊份子的實際行動來回應:我用抵禦的姿態來拒絕自己被觀察、被記錄、被描述;我用抵禦的姿態來宣示自己的位置,而我就在這裡,用自己的方式逃開你的凝視,以及你的相機。

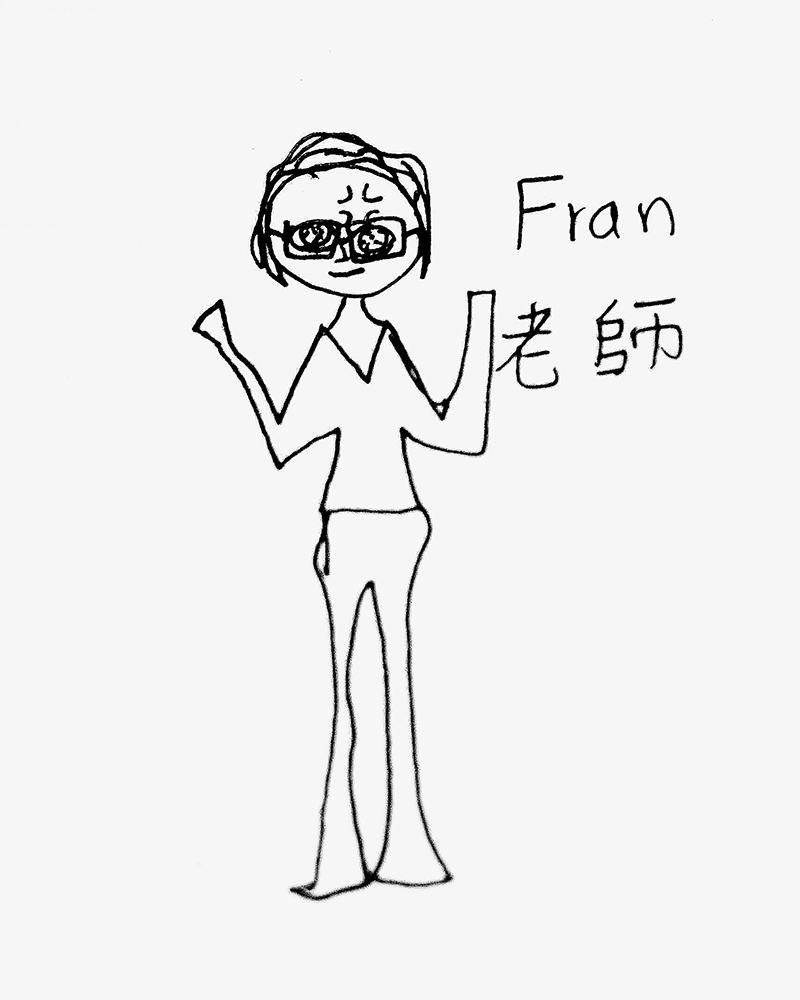

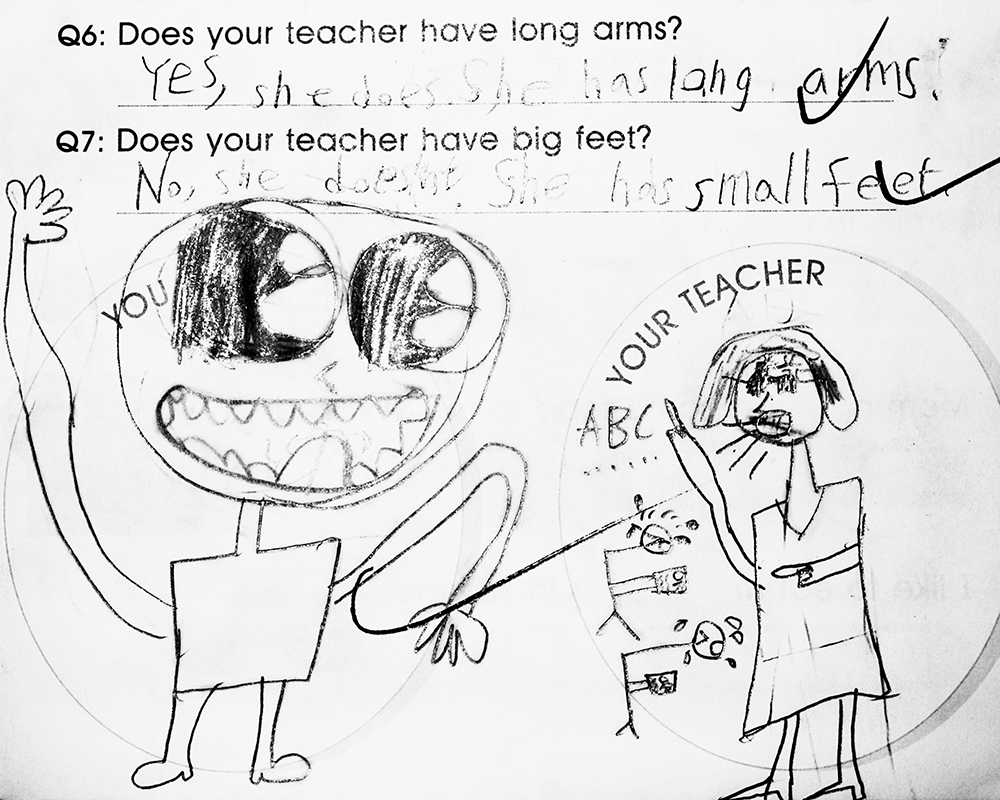

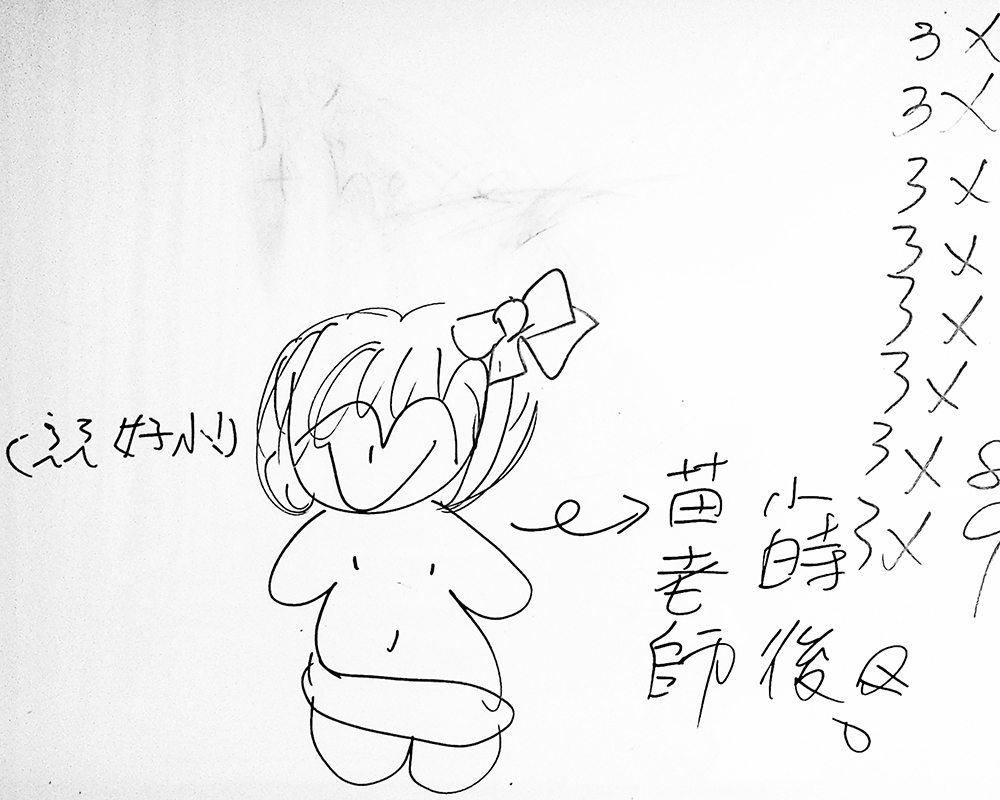

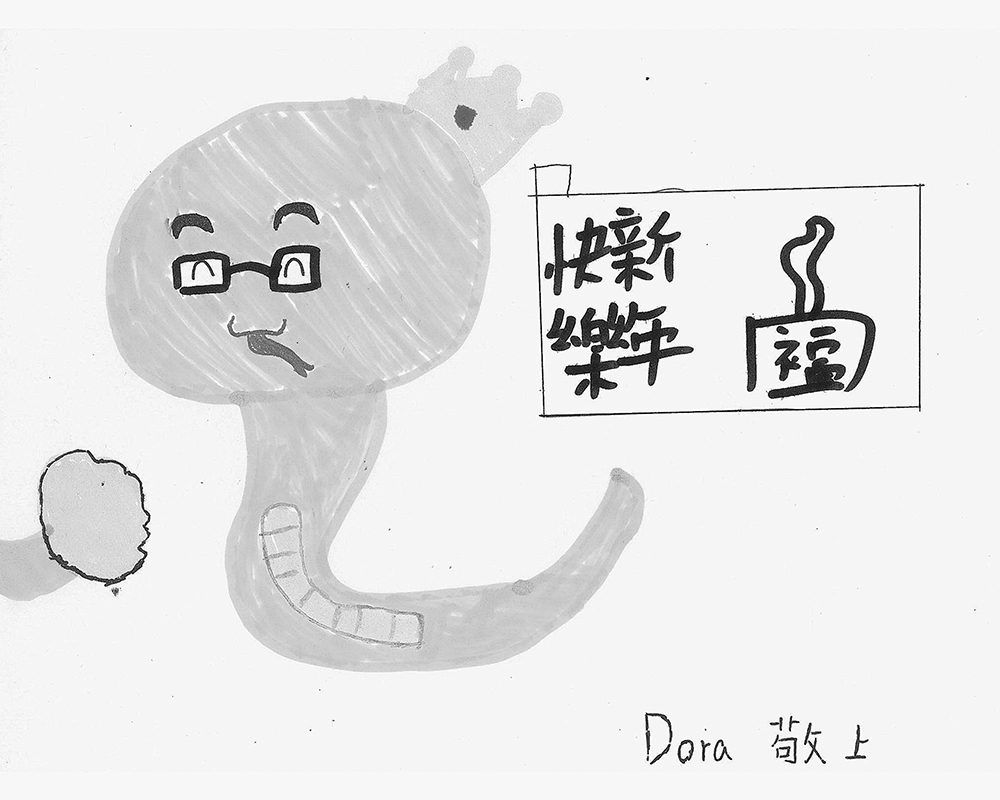

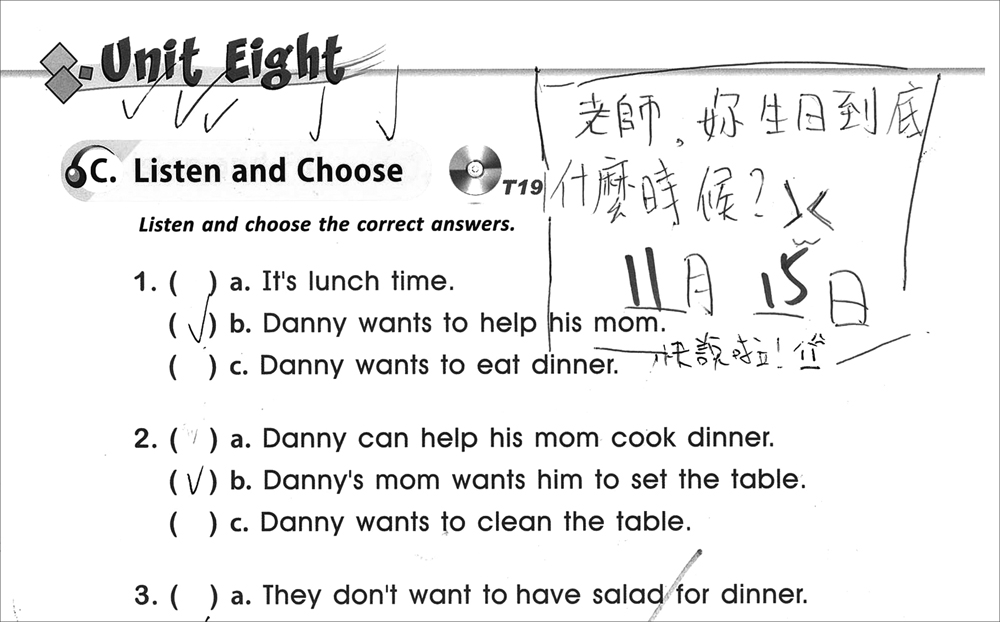

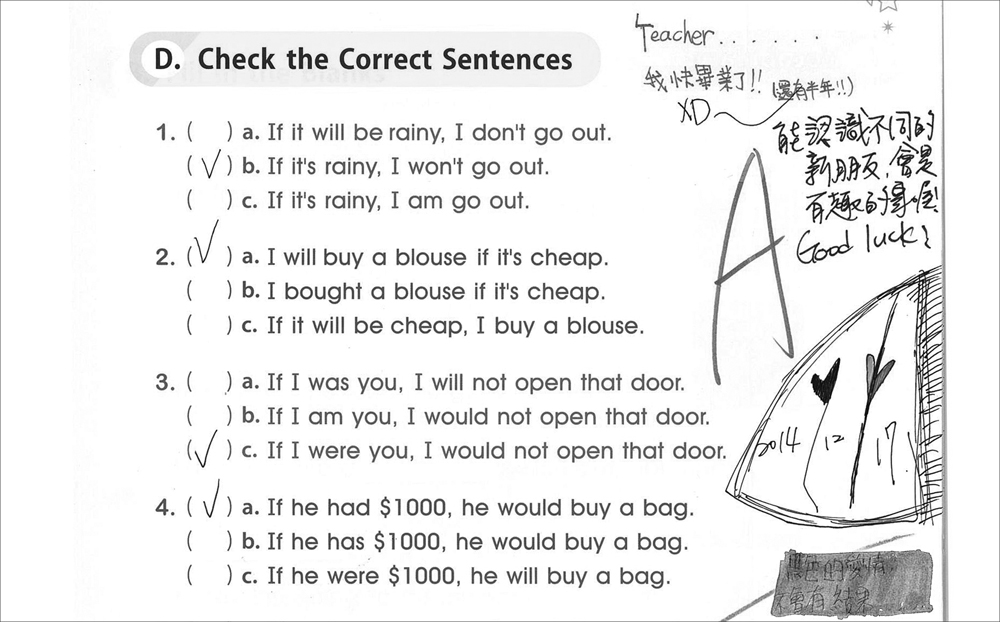

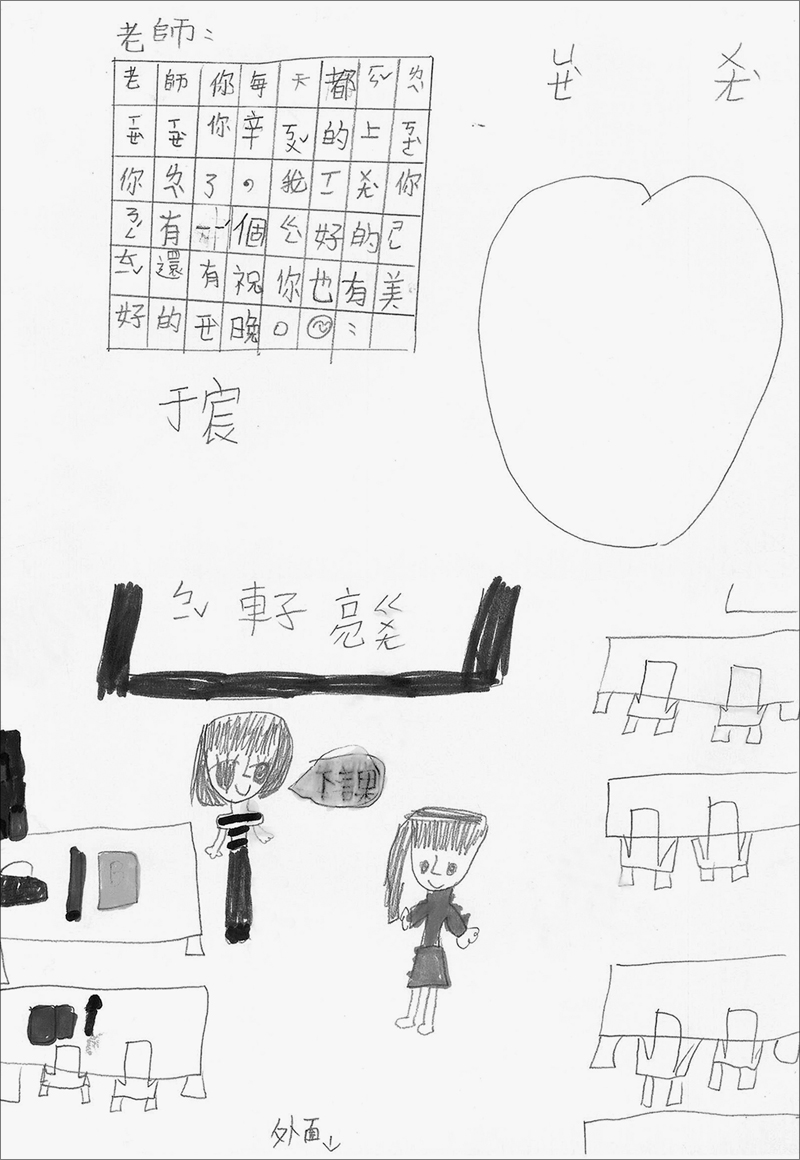

隱形在教室內的權力翹翹板因此滑動起來,不再只倒向老師/攝影者/大人的這一端。每一次有如嬉鬧般「對準後拍攝」(point and shoot)的衝突時刻,理應作為證據的照片,證明的卻是捕捉真實瞬間的意圖落得可笑、翹翹板的反向傾斜、權力的撤退。老師這雙「由上往下」凝視的雙眼,回過頭來也被觀察著、描繪著。偶然在一份學習單的背面,我初次看見自己如何被那些「由下往上」看的眼睛所觀察:啊,一個手足無措的大人、頭爆青筋的老師、失敗的攝影者!

已故法國思想家德塞圖(Michel de Certeau)曾言:「小孩在教科書上潦草寫畫、塗鴉,即使他會因此受罰,他已經為自己創造了空間,讓自己以作者一樣的方式標榜自身存在。」也就是這樣的「空間」和「存在」,學生在教室裡教了我,身為一個老師,最重要的一課。

The Classroom Project (2009-2015)

Statement

The classroom is a site of power struggle in a micro sense.

As a part-time language teacher, a photographer, and an adult, I am on the side of the power. My students - children and to be photographed - stand on the other side.

Almost accidentally, I started to take photos of naughty or bad behaved students during the classes. I intended to show these photos as the evidences to their parents that how they acted in my classes. However, I suddenly realized that what I did was aggressive in many ways when I held my camera and pointed at them.

Nevertheless, capturing the naughty or bad behaviors by my camera did not show the so-called “truth.” The photographer, me in this case, who believed the photos could tell facts and show evidences, had nothing but my own absurdity. No deceive moments. Nothing was photographed. There were only happy suspects, their unrecognized faces, resistance, and escape.

It is the gesture of denial and resistance makes me reconsider and introspect my roles in this game. These young guerrillas in my photos rejected to be observed and described by showing their counteraction and evasion. They declared where they were by this specific gesture, and they revealed that they did have ways to escape from my camera and my gazes.

The invisible seesaw in the classroom started to move, and the students’ end went down while the teacher’s end went up. Or put it in this way: the teacher fell back as the students advanced. How ridiculous it was to believe that my camera could capture the crucial moments. Though my eyes observed and looked downward at them, I was observed and depicted by those eyes that looked upward at me in return. I found myself sketched by a child on the back of a study sheet, on which the comic figure was irritated and annoyed. That was me, a childish adult, an angry teacher, and a failed photographer.

The late French philosopher Michel de Certeau once said, “The child still scrawls and daubs on his schoolbooks; even if he is punished for this crime, he has made a space for himself and signs his existence as an author on it.” It is the space and the existence in the classroom that teaches me, as the teacher, the most important lesson.